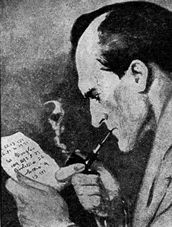

Ever since I was a boy, I desperately wanted a magnifying glass, a double brimmed deer-stalker hat and a curved tobacco pipe like the iconic image of Sherlock Holmes. I still enjoy the stories of Holmes. I find Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's stories to be extraordinarily entertaining.

Ever since I was a boy, I desperately wanted a magnifying glass, a double brimmed deer-stalker hat and a curved tobacco pipe like the iconic image of Sherlock Holmes. I still enjoy the stories of Holmes. I find Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's stories to be extraordinarily entertaining.The Holmes stories are one of the most popular and enduring serial stories ever published. Doyle wrote the stories for a periodical magazine called The Strand. The success of the series was partly due to the form in which the stories appeared. The Holmes stories are written “first person narrative” from Dr. Watson’s perspective. Watson is not only a character and participant in the adventures of Holmes, but also the reader’s personal guide. Since Watson is an old friend of Holmes, we the reader are able to see Holmes through his accustomed eyes. Holmes instantly becomes a man who we are familiar with. Combined with this familiarity, however, is an enduring sense of mystique. For although Watson is an old friend—who lived as a bachelor with Holmes for quite some time—Watson still doesn’t really “know” Holmes. As Holmes’ behaviour and genius surprises Watson, so he surprises the reader. As narrator, Watson is also able to ask the questions we, the readers, would like to ask Holmes. “How did you figure it out, Holmes?” Watson asks. Holmes then gives Watson—and us—the answer.

Since Watson is both an observer as well as a participant, his narrative is given additional credibility. The adventures are more realistic, since they are told by a first-hand witness. Because Watson is a Doctor, his approach to recording the adventures of Sherlock Holmes is accurate and methodical. I am reminded of Dr. Luke and his account of the adventures of the Apostles Peter and Paul. Like Luke, Watson pays close attention to detail and records these details as plainly as he witnesses them.

Watson also acts as a “foil” for Holmes. Watson is in many ways the exact

opposite of Holmes; as much as Holmes is extraordinary, Watson is ordinary. The reader can relate to Watson: he is married, he keeps ordinary hours, he enjoys a good meal, he is concerned with people. Watson’s humanity is set against Holmes’ purely logical mind. Holmes is never interested in a case because of the people involved unless there is some curios aspect about them; he is motivated by the case itself, the mystery. He is a scientist of the truest sense. Watson, who is a medical doctor, is less interested in the science of medicine as with helping people with the science of medicine. So Watson provides not only contrast, but also balance to the Holmes’ adventures.

opposite of Holmes; as much as Holmes is extraordinary, Watson is ordinary. The reader can relate to Watson: he is married, he keeps ordinary hours, he enjoys a good meal, he is concerned with people. Watson’s humanity is set against Holmes’ purely logical mind. Holmes is never interested in a case because of the people involved unless there is some curios aspect about them; he is motivated by the case itself, the mystery. He is a scientist of the truest sense. Watson, who is a medical doctor, is less interested in the science of medicine as with helping people with the science of medicine. So Watson provides not only contrast, but also balance to the Holmes’ adventures.Holmes is not inhuman though. We see glimpses of his humanity when he plays his violin or when he is on a heroine binge. We can relate to his need for a “thrill”—whether it be solving a strange mystery or from a narcotic. In some ways, we the readers are addicted to Holmes himself. He is an intoxicating character.

The Watson-Holmes appeal rests also on the simple fact that we love to read about this wonderful friendship. Some of the greatest stories in English literature celebrate friendship. There’s Sam and Frodo, Crusoe and Friday, George and Lennie, Ralph and Piggy, Harry and Falstaff.

Holmes never actually said, “Elementary, my dear Watson”—but, Doyle could have very well said it himself. He created one of the most enduring yet elementary and formulaic story-characters of all time.

No comments:

Post a Comment